Some of the Newer Organizational Designs Might Improve the Organization

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

1 Organizational Change and Redesign

Organizational change is pervasive today, as organizations struggle to adapt or face decline in the volatile environments of a global economic and political world. The many potent forces in these environments—competition, technological innovations, professionalism, and demographics, to name a few—shape the process of organizational adaptation. As a result, organizations may shift focus, modify goals, restructure roles and responsibilities, and develop new forms. Adaptive efforts such as these may be said to fall under the general rubric of redesign.

In this chapter, we examine aspects of organizational environments that research and practice suggest are changing and are causing managers to redesign their organizations. We discuss the effects of increases in scientific knowledge, societal trends in professional roles, and changing technologies and demographic trends on organizations. We then examine several bases for organizational design and redesign: the work of organizational theorists, the practical experience of managers, and the precepts of doctrine. Finally, we consider new organizational forms as a response to environmental change.

Environmental Conditions Driving Organizational Change

The committee's reading of organization theory and managerial wisdom suggests that, for an organization to survive, it must be compatible with its environment, i.e., all external social, economic, and political conditions that can influence the organization's actions, nature, and survival.

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

When the environments change, the organization must eventually respond, and today this must occur at a rate and in ways never before seen or imagined. Organizations that are not able to adapt quickly enough to maintain their legitimacy or the resources they need to survive either cease to exist or become assimilated into other organizations.

Perhaps the most noteworthy change in the environment for business organizations has been the dramatic shift in the developed world from an industrial to an information economy. In 1991, for the first time ever, companies spent more money on computing and communications gear than on industrial, mining, farm, and construction equipment combined. In the 1960s, approximately half of the workers in industrialized countries were involved in making things; by the year 2000, it is estimated that no developed country will have more than one-eighth of its workforce in the traditional roles of making and moving goods (Drucker, 1993). But this is only the most obvious of the trends that are redefining the nature of contemporary organizations.

Population ecology, as its name implies, focuses on the changing nature of populations of organizations (Hannan and Freeman, 1977; Hannan and Carroll, 1992). Institutional theory focuses on the need for organizations to maintain legitimacy with societal norms and values, often embodied in governments, professions, and trade associations (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; Powell and DiMaggio, 1991; Scott, 1987, 1995; Zucker, 1977). Both of these perspectives are fruitful. They tend, however, to deemphasize the influences of management action and leadership in organizational change (but see Hannan and Freeman, 1984; Suchman, 1995). In this chapter, in contrast, we emphasize the role of managers as interpreters and even manipulators of their organization's environment. We emphasize in particular the idea that managers change and redesign their organizations primarily in order to adapt them to changes in the environment, but also to adjust them to changes in the managers' own aspirations and perceptions, or to unintended or unmanaged changes within the organization. Thus, whereas organizational environments and processes are often sources of change, we adopt the strategic choice point of view (Child, 1972), the idea that organizations vary in their choice of responses, the timing of their responses, and the means and effectiveness of executing their responses, and that these phenomena are managerially determined to a great extent.

Some of the most powerful forces identified by the business press and organizational literature that are motivating managers to redesign their organizations are the increase in scientific knowledge, changes in professional roles, the technology explosion, and the changing demographics of the American workforce.

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

Increase in Scientific Knowledge

There are strong reasons to believe that growth in the world's store of scientific knowledge is a long-term trend that can help to explain the changing nature of organizations. This environmental change is both long-term and antecedent. Consider, as an indicator of scientific knowledge, reports of scientific findings. From 1965 to 1980, the number of scientific articles published per day grew from 3,000 to 8,000, a 160 percent increase (Huppes, 1987:65). This increase is only a snapshot measure of the long-term trend in the generation of scientific knowledge. To get an idea of the longer trend, consider the accelerating increase in the number of scientific journals recorded by De Solla Price (1963). The first 2 scientific journals appeared in the mid-seventeenth century; by the middle of the eighteenth century there were 10 scientific journals, by 1800 about 100, by 1850 about 1,000. Recently, Goodstein (1995) stated that there are currently about 40,000.

These increases in scientific knowledge can be attributed to previous increases—knowledge feeding on itself—to increases in the size of the scientific community, and to increases in effective means of distributing scientific knowledge. Although exponential growth cannot continue forever, this general pattern of rapid growth is likely to continue into the intermediate future.

One reason to expect continued growth in scientific knowledge is that increased capability and application of advanced communications technologies will greatly increase the availability of whatever knowledge is produced. Even now, a weekday edition of The New York Times contains more information than the average person was likely to come across in a lifetime during the seventeenth century, and it is estimated that today the amount of information available to the average person doubles every five years (Wurman, 1989). In addition, reflecting on advances in information technologies during the last 50 years makes clear that (1) such technologies are still in their early stages of effectiveness or adoption and (2) other, better, technologies are in the making. Consequently, the availability of existing knowledge will increase as the technologies mature and become more widely used. Increased adoption of these knowledge-distributing technologies, in conjunction with the ongoing acceleration in the size of the knowledge base, will result in a knowledge environment that will be dramatically both more munificent and more burdensome than that confronting organizations today.

Increases in scientific knowledge have important practical impacts. For example, globalization, which may be the most important economic phenomenon of the 1980s and 1990s, is possible only because of advances in communication and transportation technologies. Advances in these technologies follow, in turn, from increases in scientific knowledge. Increases in scientific knowledge are therefore a root cause of change in organizational

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

environments. This is much more true today than in earlier eras, when technological advances were more likely to result from localized insights and atheoretic experimentation rather than following from the worldwide accumulation and consolidation of scientific advances (Heilbroner, 1995; Mokyr, 1990).

Ultimately, we are interested in changes, even improvements, in organizational performance. The question is which features of an organization's environment, when they change, force changes in the organization itself, and hence alter its performance. The committee's reading of the literature suggests that there are three such features: environmental complexity, environmental turbulence, and environmental competitiveness.

Complexity arises not only from improvements in communication and transportation technologies but also from increases in both diversity and specialization, leading to interdependencies among organizations—that is, increased complexity of any single organization's environment and some loss of control by that organization. Environmental turbulence results from the fact that individual events happen more quickly—for example, the ever-shortening product life cycle. Environmental competitiveness arises from a number of factors, including new products competing with old ones, the removal of distance barriers that provided buffers from competition, and improved information technologies that enable producers of goods and services from far away to compete with local establishments for customers and clients. Organizations adapt to these changes by making decisions more frequently, more rapidly, and in more complex ways; by implementing decisions more rapidly; by requiring information acquisition to be continuous and more comprehensive; by reinforcing more selective information distribution; and by promoting more effective organizational learning (Huber, 1984; Huber et al., 1993).

Trends in Professional Roles

Changes in the concept of the professional and the development of professionalism have important implications for organizational forms and management structures. A profession is a calling requiring specialized knowledge and often long and intensive academic preparation. The concept further implies career and commitment to service, rather than casual employment and reliance on external incentives alone, and belief in collegial, rather than hierarchical, control of professional behavior. The concept of the professional was developed, beginning in the Middle Ages, to describe a special set of emergent occupations—freestanding, solo, private practice, and self-employed (Abbott, 1988).

Increasingly, however, the professions are being transformed from freestanding occupations to positions embedded in organizations, with important

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

implications (Kornhauser, 1963; Abbott, 1988). This movement of professionals into organizations is neither uniform nor complete, nor is it likely to become so. As a result, members of the same profession now find themselves variously located in the societal structure of work—some in traditional solo practice; some in small groups or not-so-small professional organizations of their own construction, in which the professional service is the main organizational product; and some as staff specialists in organizations whose primary products or services are not those of its professionals. The first of these categories is familiar; the second is exemplified by the multilawyer legal firm and the medical group practice or health maintenance organization. Finally, the embedding of professional specialists in more conventional organizations is represented by the legal and medical departments of an automobile corporation.

Almost equally significant is the emergence of new professions, many of them created as part of a more general process of technological development. Computer-related expertise is among the most conspicuous examples of a new profession.

The movement of professionals into organizations involves an inherent tension between professionals and managers. Conventional organizations are basically hierarchical, and their governance is internal. Even managements that are enlightened about the advantages of delegation and employee participation in decision making operate on the assumption that authority is exercised through a sequence of supervisory levels, each of which can in principle overrule those below it. Moreover, this governance structure is almost wholly internal, although some intrusion from the outside world is discernible in corporate control. All organizations are required to conform to legal statutes; some must share power with labor unions; and corporate boards typically include some outside members. But the basic policies are internally determined, typically at or near the top of the organization, and overseeing their implementation is the responsibility of successive layers of management and supervision.

This is in marked contrast to the principles of individual autonomy and collegial control that are the hallmarks of the professions. As organizations have made increased the use of professionals, they have found it necessary to make significant changes. Professionals in organizations are not usually subject to the form and degree of supervisory control that is exercised over other nonsupervisory employees. As Freidson (1986) points out, managers do not specify directly the pace and method of professional work, although overall deadlines for project completion may be imposed or attempted. Most managers, unless they are themselves professionals in the same field as those they supervise, recognize their lack of expertise for imposing detailed controls over the work of professionals. But management allocates resources among competing claimants, and in this respect different professional

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

groups are in competition with each other and with other functional subsystems of the organization.

Even organizations with high proportions of professionals require hierarchical decision authority to some extent, although they tend to be less centralized and are characterized by greater structural complexity (Hall, 1968; Trice and Beyer, 1993). Incompatibilities between the level of professionalism and the organization's design are associated with lower levels of organizational effectiveness (Huber et al., 1990).

Emerging Technologies

Changes in technology, broadly defined, have three important implications for organizational design. First, in the form of automation, the use of technology has had visible effects on the structure of organizations. Automation enables an organization to grow in terms of its output and impact (e.g., customer transactions per day in a bank, cans of peas produced per hour in a factory), while shrinking the number of personnel. Automation is often linked to a deskilling of the workforce, although new technology can also be associated with increases in the ratio of skilled to unskilled workers, as computer programmers, missile guidance technicians, and machine setup personnel are called on to maintain or interact with equipment that replaced bank tellers, cannoneers, and assembly line operators.

Often the ''upskilling" of personnel reduces the number of persons coordinated by managers at the next hierarchical level, as the work tasks become more difficult to understand and to coordinate, even as the personnel themselves become more specialized and expert. Thus, although automation decreases the number of operating personnel, the number of vertical levels in the organization may not decrease accordingly, and this changes the shape of the organization.

Second, the use of computer-assisted communication and decision-aiding technologies tends to lead to changes in organizational design and decision processes (Quinn, 1992). Recent reviews (Brynjolfsson and Yang, 1996; Fulk and DeSanctis, 1995), theory-building efforts (Huber, 1990), and empirical works (Brynjolfsson et al., 1994; Leidner and Elam, 1995; Scott Morton, 1991) support the idea that the use of computer-assisted communication technologies (e.g., electronic mail, voice mail, visual image transmission devices, computer and video conferencing) and decision-aiding technologies (e.g., expert systems, decision support systems, spread sheets) affect organizational design and organizational decision processes, such as facilitating the elimination of layers of management and enabling the effective functioning of network organizations composed of other organizations. There is still considerable question, however, as to whether they create positive

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

effects on performance, through their effects on organizational processes and structures (Harris, 1994).

Huber (1990) argues that they do. Synthesizing findings from several literatures, he concludes that, through their effects on organizational processes and structures, the technologies have positive effects on the acquisition and development of organizational intelligence and on decision-making processes. An example is provided by the air offensive against Iraq during the Persian Gulf War in 1991, during which information technology was used in allocation decisions—for example, decisions for allocating missions and weapon systems to Iraqi targets and for revising such allocations in light of communications (ranging from pilot observation to satellite data processed in the United States) about the effects of previous missions. Given that 30,000 missions were flown in less than two weeks (Schwarzkopf, 1992:240), it is difficult to imagine that the computer-aided decision support and communication system did not outperform what would have been possible in the past with decision makers who were not aided by modern information technology. Nevertheless, several studies, such as those by Loveman (1994) and Morrison and Berndt (1990), have found no effects or a negative effect on performance despite the fact that businesses around the world spend billions each year on information technology in the form of hardware, software, and support personnel.

Some explanation for the gap between expectations for the technology and its apparent performance may be found in the studies themselves, namely in measurement difficulties and sampling problems (Brynjolfsson, 1993). But a good part of the explanation may be simple cultural lag. Introduction of new technologies requires immediate capital investment and training costs. The benefits may be years in coming. The organizational learning required to know how to use the technology or to redesign work and managerial structures to take advantage of the technology is substantial.

The third area in which technology has had a strong impact on organizational change is that of the so-called high-risk technologies. Despite impressive improvements in safety technology in recent years, the number of accidents associated with new technologies has risen dramatically, along with the potential for enormous loss of life and property, environmental devastation, and economic costs. Examples are the Tenerife air disaster; the Three Mile Island and other nuclear accidents; the Bhopal, India, chemical accident; the Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill; and the Challenger launch explosion. Each of these disasters is associated with an organization's use of technology to achieve difficult, challenging goals that would be impossible to achieve manually.

Dependence on technology that brings with it potential risks is leading to the creation of a new type of organization—the high-reliability organization. The idea is to design organization specifically to manage the serious

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

risks associated with the use of technologies that, if they fail, can have extremely serious consequences (Roberts, 1993). It is a complicated undertaking. A major characteristic of advanced and automated technologies is that their operators and managers are increasingly remote from the processes for which they are responsible. With older technologies, operators could see and touch what they controlled or produced. Mechanisms like gears and pistons were visible, and their action and means of control were obvious. Mental images of the way things worked and how they could go wrong were easily learned and readily shared. People, alone and in teams, were an integral part of the control loop that made these technologies run.

With the advent of remote sensing, computing, and automatic control, the role of the operator is shifting from that of direct sensor and controller to that of monitor and supervisor. Machine intelligence can either augment or displace human intelligence. All too often automation becomes the first line of defense. The human is moved to the periphery of the control loop but then is expected to intervene when safety systems fail.

Unfortunately, people are notoriously poor at monitoring and detecting low-probability events and are fallible in making decisions under stress. Inadequate engineering of the human-system interface sets people up to make errors in diagnosing and managing the systems that automatic systems have failed to control (Sagan, 1995). Thus, we are faced with a paradox: while human intelligence and decision making are being supplanted by automation, humans and human organizations nevertheless represent a last line of defense in the detection of faults and the management of emergencies when automatic safeguards fail. This is the challenge to be met by those who would posit or create the high-reliability organization.

The Changing U.S. Population

The final factor driving organizational change discussed in this chapter is shifts in the structure of the U.S. population. Increased life expectancy, increased racial and ethnic diversity—both in the U.S. population as a whole and in its labor force—and the increased labor force participation of women not only generate new demands on organizations but also offer new opportunities. How those challenges will be met and with what consequences for the performance of organizations, the competitiveness of industries, and the quality of life in the United States remains to be seen.

To say that the effects on organizational design of demographic diversity in organizations are well documented or synthesized would be a gross overstatement; there are some bodies of evidence concerning the effects on organizational processes, however. One is the body of literature indicating that demographic diversity contributes to higher-quality decisions in decision-making groups, provided it is not so great that it leads to a breakdown

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

in group functioning (Cox, 1993; Griggs and Louw, 1995). Another is the idea that high levels of diversity are associated with lower levels of cooperation and proactive social behavior, an idea that follows from findings that demographic diversity is negatively related to interpersonal communications and positive relationships (Jackson et al., 1993) and that such communications and relationships, especially with supervisors, are positively related to cooperation and proactive social behavior (Wayne and Green, 1993). At present the field has little basis for a theory of how these phenomena affect organizational performance in a given situation (but see Cox et al., 1991; Golembiewski, 1995; O'Reilly et al., 1993).

What seems more certain is that an organization with demographically diverse stakeholders is better able to satisfy stakeholder demands if its decision makers, and members who interact with its stakeholders, include personnel whose demographic composition resembles that of the stakeholders (Cox and Blake, 1991).

We turn now to an examination of organizational design and redesign, which are influenced in important ways by these environmental conditions.

Organizational Design And Redesign

An organization's design refers to its particular configuration of organizational characteristics. These characteristics include structural dimensions, such as size, number of vertical levels, and degree of specialization among organizational units or personnel. Other organizational features, such as culture, primary operating processes, and even strategy, are also included in the concept of organizational design. Because many more organizations are changed each year than are founded, much of organizational design is actually redesign. Redesign is usually an intensively managed endeavor, as illustrated by the well-known redesigns at General Electric and Xerox. Both of these redesigns involved comprehensive changes in strategy, technology, staffing, and culture.

Because there are an immense number and great variety of characteristics on which organizations can differ, a great number of organizational designs are possible. The actual number of significantly different designs found in any population of organizations, however, tends to be much smaller than the theoretical possibilities. This is because many combinations of organizational characteristics or features are not workable or result in inferior performance and are selected out of the population. It is also because, once organizational forms are established and appear to be effective, many will tend to quickly copy them. In contrast, other designs result in smooth and effective organizational functioning, that is, in high levels of organizational performance. Eventually, these latter patterns or clustering of organizational characteristics become more frequently observed.

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

Organizational scholars and practicing managers have given names to the more common organizational forms. Based on the work of Mintzberg (1993), Table 1-1 outlines four "pure forms" of organizational design. Hybrid combinations of two or more pure forms also occur; the matrix structure, for example, often combines the functional form and the team-based form. Other organizational forms are combinations of somewhat independent organizations; Table 1-2 outlines four such "supraorganizational" forms.

Although the forms described in the two tables and the more common hybrids can be observed, the actual designs of almost all organizations depart from these pure forms. Whether by accident or intention, the evolved composite of a series of design decisions causes actual designs to be idiosyncratic. This fact raises an interesting question: What are the sources of managerial knowledge or belief that cause design decisions to be what they are? The remainder of this chapter addresses this question. We begin by discussing systematically derived theory as a basis for organizational design.

Organization Theory as a Basis for Design and Redesign

Shortly after the beginning of the twentieth century, behavioral scientists began conducting empirical studies of the determinants of human and organizational performance, such as the famous Hawthorne studies at Western Electric (Roethlisberger and Dickson, 1939). Especially after World War II, psychological and sociological studies of behavior and performance within organizations became more theory driven, more methodologically sophisticated, and more numerous. These studies have resulted in descriptive theories about the organizational-level factors and features that determine organizational performance. The best-known of these is called contingency theory; with its extension, configuration theory, it is the basis for most recommendations for organizational design made today by organizational scientists and many management consultants (Burke and Litwin, 1992; Lawrence, 1993; Burton and Obel, 1995; Galbraith, 1977).

Contingency Theory and Configuration Theory

Early work in organizational science focused on the need for an appropriate alignment (i.e., fit or match) between an organization's structure and its environment. This idea was called contingency theory—the appropriate structure is contingent on the environment. For example, organizations with low levels of centralization and formalization are more effective in turbulent environments, whereas organizations with high levels of centralization and formalization are more effective in placid environments. As organizational scientists continued investigating relationships between pairs

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

TABLE 1-1 Four Most Common Organizational Designs

| Characteristic | Simple Structure | Functional Form/Machine Bureaucracy | Professional Bureaucracy | Adhocracy/Team-Based |

| Primary control mechanism | Direct supervision | Formalization of standards | Professional standards | Mutual adjustment |

| Specialization of jobs | Little specialization | Much vertical and horizontal specialization | Much horizontal specialization | Much horizontal specialization |

| Flexibility to adapt to environmental change | High | Moderately high if top management is sensitized to need for change, how otherwise | Low | High |

| Most favorable environment | Simple, fast-changing | Simple or complex | Simple or complex, stable | Simple, fast-changing. |

| Examples | Start-up firm, small unit patrols in enemy-held terrain | Large hotel, military procurement organization | University, military research organization | Performing arts theater, product design team |

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

TABLE 1-2 Three Most Common Supraorganizational Designs

| Characteristics | Multidivisional | Prime Contractor/Subcontractor | Network or Virtual Organization |

| Component organizations | Headquarters and subordinate divisions | Prime contractor and independent subcontractors | Broker and partner |

| Primary control mechanism | Comparison of divisional performance, allocation of budgeted resources | Adherence to contractual agreements, parties have options not to continue relationship after each contract cycle | Adherence to contractual agreements, need to maintain reputation for cooperative behavior |

| Horizontal interunit competitiveness | High | High within specialties, low otherwise | Low |

| Most favorable environment | Stable | Stable | Fast-changing |

| Examples | Automobile company, Army corps | Aerospace firm military base | Multifirm alliance for major construction project, military joint-service operation/exercise |

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

of other variables (e.g., Woodward's 1957 study of the relationship between manufacturing technology and organizational structure), it became clear that performance is related to the match between particular pairings of organizational features, such as strategy, structure, technology, culture, human resources, leadership, and environment. One of the more practical prescriptive contingency theories is organizational information-processing theory (Huber, 1982; Tushman and Nadler, 1978). In its prescriptive form (see Galbraith, 1977), this theory offers guidelines for designing organizations such that organizational processes and structures are congruent with the nature of the information-processing load imposed by the organization's environment. for more general references to prescriptive guidelines following from contingency theory, see Burton and Obel (1995) and Lawrence (1993).

More recently, perhaps as an extension of systems thinking (Katz and Kahn, 1978), the importance for performance of a simultaneous fit among all organizational characteristics as well as with the organization's environments has become clear (Miller, 1981, 1987; Van de Ven and Drazin, 1985). This idea is the basis for configuration theory. Miles and Snow (1978), for example, articulate the necessity of simultaneous congruence across an organization's strategy, production processes, and administrative structure. In recent years, configuration theory has been advanced both conceptually (Burke and Litwin, 1992; Doty and Glick, 1994; Meyer et al., 1993) and methodologically (Doty et al., 1993; Drazin and Van de Ven, 1985). Although not necessarily labeled as such, configuration theory is becoming dominant in theory-based organizational design (see Burke, 1994; Miles and Snow, 1994; Mintzberg, 1993).

Theories of Organizational Change

While numerous organization theories deal with organizational change—including population ecology and institutional theory (mentioned earlier), which emphasize why change is so difficult to accomplish—we examine here two theories about organizational redesign that more clearly depend on managerial action. One of these we term the evolution and revolution theory of organizational change. It addresses the rather qualitative difference between evolutionary change, in which incremental adjustments to an organization's characteristics are made over long periods of time in order to align these characteristics with each other and with the organization's environment, and revolutionary change, in which all features are changed radically and simultaneously, generally to realign the organization with its environment. This theory, the organizational science version of Gould and Eldredge's (1977) "punctuated equilibrium" theory, seems to have considerable potential for the field of organizational redesign.

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

The evolution and revolution perspective on organizational change is still in its youth and perhaps should be recognized only as a theory in the making. Early researchers in the area (miller and Friesen, 1980; Tushman and Romanelli, 1985) continue to extend and influence its development (Miller, 1987; Tushman et al., 1986), but findings by other researchers unaffiliated with these early pioneers also confirm and elaborate the central thrust of the work (Amburgey et al., 1993; Gersick, 1994). This perspective and body of work seems likely to gain influence in organizational redesign for three reasons: (1) its thrust is relevant to today's changing organizational environments, (2) few executives have the opportunity to acquire the breadth or length of experience necessary to learn its lessons on their own, and (3) early indications are that some of its prescriptive guidelines will not be intuitively obvious.

Another theory of organizational change is life-cycle theory (Greiner, 1972; Kimberly et al., 1980). It describes how different features of an organization change more or less in harmony as organizations mature. For example, as organizations mature, they become more internally specialized and consequently need more coordination processes, personnel, and units.

Life-cycle theory seems to have received acceptance largely on the basis of case studies (Kimberly et al., 1980), although some larger sample studies have supported the concept of stages that reflect congruent characteristics (Miller and Friesen, 1984; Quinn and Cameron, 1983) but not the idea that the sequence of stages is fixed. It seems plausible that combining two ideas—that there are phases within an organization's life cycle and that there should be congruence among the organization's features within each phase—can lead to prescriptive organizational redesign guidelines for improving performance.

We close this section on theories of organizational change by mentioning two related bodies of literature. One is the large literature on organizational development (Burke, 1994; French and Bell, 1990), which focuses primarily on organizational change for improving the quality of working life in organizations; for a review of this literature, see Faucheux et al. (1982) and Beer and Walton (1987). The other is the relatively newer and smaller body of literature on organizational learning (see Cohen and Sproull, 1996). Reviews by Huber (1991) and Levitt and March (1988) indicate that research on organizational learning has not yet become systematic. The potential for development of prescriptive guidelines seems high; an early attempt at this is the best-seller by Senge (1990).

Experience as a Basis for Organizational Design

Individual managers can learn from their experience in an organization about the appropriateness of its design by seeing and hearing about defects

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

in the design. In addition to learning about organizational designs and their efficacy by comparing different organizations, managers may learn by observing the defects of changed designs in their own organization. Sometimes individual organizations change to mimic certain features, such as designs, of other organizations that are considered to be leaders (Tolbert and Zucker, 1983). Changes enable managers to observe before-and-after pairings of design and performance and, hence, to learn. Of course, a variety of factors limits the validity of such learned relationships. Some of these are difficulties associated with all human learning, including cognitive and motivational biases (Bazerman, 1986; Mayer, 1992). Others have to do with the problems of verticality in organizational information flows (Huber, 1982), such as inadvertent distortions at multiple nodes in a communication network and deliberate distortions by those who seek to gain from such distortions. A manager who observed a large number of design changes might be less prone to learning incorrectly by making comparisons or averaging across instances, but few managers experience a large number of organizational changes that are comparable.

Some of the difficulties associated with firsthand observation of a very limited number of pairings of organizational design and performance are overcome by managers through vicarious learning. Managers talk with other managers in other companies, they talk with consultants who themselves have had many opportunities to observe design-performance pairings, and they read the business press reports of organizational design and performance pairings in individual companies. Although there is little research on managerial learning through these media, we speculate that managers do learn about alternative ways of organizing this way. We also speculate that due to the absence of useful frameworks about organizational designs and of specific and comparable performance data, what managers learn this way is fairly superficial and of only modest validity. Some support for these speculations is the research of Burns and Wholey (1993), who found that hospitals adopted matrix structures of organization more to follow a current fashion rather than because the structural form fitted their situation.

Perhaps the most obvious way for a manager to extend his or her own experience is to consult an expert, a person who has seen more design alternatives and has been in a position to evaluate them. Individual consultants and consulting firms vary greatly in the extent to which they accumulate and codify their experience, however. Authors and consultants are overlapping categories; many authors are also consultants, and their experience in that role informs their books. And in some cases, their ideas about organizational design are also shaped by specific theoretical models and research.

This combination is well exemplified by the best-seller on organizational

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

design and practice, In Search of Excellence, by Peters and Waterman (1982). Both authors were members of a large consulting firm, McKinsey and Company, and both were experienced consultants. They worked within a schema, the McKinsey 7-S framework, which is more a listing of classes of factors to take into account than a theory of organization. The framework consists of seven factors that in combination are assumed to determine organizational effectiveness. All seven are drawn as interconnected and all are identified by words beginning with the letter S, hence the copyrighted 7-S label: structure, systems, style, staff, skills, strategy, and shared values. These at least serve to remind consultants of things to look for as they advise managements.

Peters and Waterman went beyond such a priori guides, however, in their search for excellent companies. With funding from McKinsey and from client firms, they set up a research project. They chose 75 ''highly regarded companies" and, for the 62 based in the United States, they did a retrospective performance review for the preceding 20 years and conducted structured interviews with some members of management. Six measures of growth and financial performance and a judgmental measure of innovativeness were thus added to the initial rating of "high regard." The use of all these criteria produced a set of companies considered exemplars of excellence: Bechtel, Boeing, Caterpillar Tractor, Dana, Delta Airlines, Digital Equipment, Emerson Electric, Fluor, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Johnson and Johnson, McDonald's, Proctor and Gamble, and 3M.

Peters and Waterman warned their readers about the limitations of their work: "We don't pretend to account for the perfidy of the market or the whims of investors. … Second, we are asked how we know that the companies we have defined as culturally innovative will stay that way. The answer is we don't" (1982:24-25). Their premonition was justified, as a third of the "excellent" companies performed poorly shortly after publication of their book (Business Week, 1984:76–88).

Doctrine as a Basis for Design

Doctrine-driven design is an approach that applies codified, normative principles to organizational design. These principles are derived from the experiences, beliefs, values, and ideologies of an organization's key leaders and are often influenced by societal values. In the long run (indeed, sometimes across generations of managers), the beliefs, values, and ideologies that become formalized into design doctrine are the result of multitudes of experiences, and the revision of doctrine in the light of experience is often a very slow process. It is important to note that the beliefs and values of an organization's leaders are often determined in great part by the larger society, and also to note that society exerts some degree of influence over the

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

doctrines of all organizations in its midst. Both of these insights are provided by institutional theory, mentioned earlier.

Clarifying the Meaning of Doctrine

The dictionary defines doctrine as a body of working principles laid down by authority, generally held to be true, and often used as the fundamental basis for instruction and training. In this section we explore the characteristics of doctrine-based organizational design in the context of military doctrine, calling attention to the fact that manifestations of doctrine are found in other organizational domains as well: government, hospitals, fire and emergency departments, power utilities, religious groups, and radical political groups.

Because doctrine-based design is generated, promulgated, and reinforced by authority, it tends to resist criticism, lag relevant events, and eventually become ineffective. Corporate doctrines can resist evidence that demonstrates their obsolescence. An example of the failure of doctrine-based organizational design is the American automotive industry of the 1970s, which persisted in adhering to an outmoded doctrine despite massive loss of market share to foreign manufacturers who had developed radically different doctrines based on such values as quality and reliability. In contrast, doctrine that is constantly reviewed and updated in response to current conditions can be a sound basis for organizational design.

Army Doctrine in the Unit Design Process 1

The U.S. Army uses doctrine in the design of its units and forces to a great extent, in a way that is important, explicit, and almost beyond question. We note that this use of doctrine in organizational design is atypical in its intensity; most organizations are influenced by doctrine in their design efforts much less intentionally and systematically.

To perform different functions, Army units must be adequately equipped and staffed with appropriate numbers of trained personnel and types of equipment. Decisions on appropriate mixes of these elements are made within the context of a broad force-structuring process initiated by the joint chiefs of staff and the secretary of defense. Design is a top-down process, and unit design provides the building blocks for this activity.2 The principal output of unit design is a set of requirements for each unit. These requirements are translated into tables of organization and equipment. The Army reviews and revises its current unit designs in response to changes in its doctrine, concepts, and new technology, as well as global trends and threats. The goal of a unit designer is to design effective units with the fewest possible resources.

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

The unit design process is part science and part art. Some capabilities required by a unit, such as the number of refueling vehicles needed to achieve specific levels of mobility, can be derived quantitatively. Others, such as the reconnaissance assets needed to carry out a mission, depend on assumptions and judgments based on experience, values, and ideology. Planning how best to organize to fight a war is an extraordinarily complex process. Hundreds of interactive considerations and contingencies must be taken into account. Here we summarize the part of this process that must go on just to organize a unit (U.S. Army, 1995).

Step 1: Identify unit design issues. In this step, all of the external conditions that are likely to affect or alter the design of a unit are identified and described. External conditions include threats (e.g., enemy missiles), revised objectives (e.g., contain versus destroy), new alliances among possible enemies, and changes in economic or political conditions that could lead to conflict. Internal conditions include new or revised missions, changing funding, technology advances, lessons learned from training and combat, and new or revised doctrine. The product of this step is a requirement to change a unit design in order to bring it up to date and tailor it to internal and external conditions.

Step 2: Develop unit design concepts. In this step, a set of design concepts is constructed given the issues, needs, and constraints that were spelled out in Step 1. The concepts identify the required capabilities for employing forces on the battlefield. They define needs but not particular means for meeting the needs. Once they have been formulated, unit design concepts drive changes in training, doctrine, leader development, and materiel requirements.

Given a requirement to design a unit, knowledge of its required capabilities, and the doctrine that will govern the performance of its mission, the unit designer draws on a knowledge base about what makes an organization effective. This knowledge base contains a number of important design principles. Design principles act as a filter to evaluate unit design alternatives. Army doctrine often suggests which principles are most relevant to a particular unit being designed. The similarity of many of these principles to those derived from organizational theory, and particularly to contingency theory, is striking.

Step 3: Analyze and test unit designs. In this step, design alternatives are examined and compared in effectiveness and efficiency. The methods used to assess effectiveness include training exercises, computer simulations, and war games. The assessment of efficiency typically centers on cost and resource analysis.

Step 4: Develop tables of organization and equipment. A table of organization and equipment lists the personnel and equipment required for

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

organizations during wartime. A "good" table reflects a balanced structure of the minimum essential personnel and equipment for a unit to accomplish its mission under conditions of sustained combat.

Step 5: Implement and evaluate the table of organization. The implementation and evaluation of tables of organization requires the integration of each unit design with other units in the force, with other services, and with allies. Ultimately, the success of the unit design process is measured by the ability of units in the field to carry out required mission tasks. Lessons learned and data collected from actual operations (e.g., Just Cause, Desert Shield/Storm) and training exercises provide feedback for the unit design process and for the revision of tables of organization. The modeling and simulation tools used in Step 3 are also applicable to this step.3

Assessment of the Bases for Organizational Design

The major sources of guidance for organizational design are research and theory, experience, and doctrine. Each of these has its own characteristics strengths and weaknesses, which are briefly outlined below.

Experience

A manager's experience can often be a poor basis for organizational design, for two reasons. One is that in some important respects the environment in which managers work is not conducive to learning. Learning is most efficient when feedback is fast and unambiguous. The outcome data from many managerial decisions, particularly changes in organizational design, are generally months or years in coming. By that time, many events, some unknown to the manager, have transpired that confound the relationship between the design decision and the outcome, thus introducing ambiguity. Furthermore, outcome data are often selectively perceived or interpreted by the managers themselves or are distorted by upward-communicating subordinates, thus rendering the feedback ambiguous, biased, or both.

The second reason is that the organizational circumstances that influenced the efficacy of a particular design in the past are not likely to be the same as those for which a new design or a redesign is contemplated. In a fast-changing world, past experiences are generally not representative of current situations. If managers have a fairly complete and accurate mental map of which contingencies influenced the effectiveness of the designs previously encountered and how the contingencies and design features interacted, account could be taken of the differences in circumstances, but this is hardly ever the case.

The experiences of management consultants may not suffer so greatly from this extrapolation problem. As we noted earlier, consultants are often

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

knowledgeable about the organizational theories that might relate contingencies, the design features, and performance, and they may incorporate these theories into their mental models. In addition, their wider variety of experiences gives them more opportunity to identify the relationships among these variables.

Prescriptive Organizational Theory

Although, to our knowledge, there are no systematic studies of the sources of ideas used by executives when they design or redesign organizations, it is generally agreed that, on the whole, theories from organizational science have had only modest impact on organizational design (Bettis, 1991; Daft and Lewin, 1990; but see Guillen, 1994), for at least three reasons. One is that organizational theories are often not very accurate when applied to a specific case (Miner, 1983; Daft and Lewin, 1990). This fact follows from the methodological problems inherent in the study of complex human systems, such as the multiplicity of performance measures and the multiplicity of causal forces. It also follows from the fact that scientists attempt to create theories that are very general and that apply to many situations. As a consequence, more broadly generalizable theoretical advances are more rewarded by the scientific community and are sought more vigorously by scientists. However, all else being equal, a general theory is less accurate about a particular situation than is a theory derived only from studies of organizations in that situation—and managers are interested in their particular situations.

Related to this issue is the matter of studying typical versus atypical organizations. The potent argument for studying atypical organizations is that by definition they have unique properties that may render general theories invalid. Some in the organizational science community are calling for more studies of atypical organizations in which mistakes can have disastrous consequences, such as atomic energy plants, toxic chemical factories, airlines and air traffic control systems, and space satellite launching organizations (Roberts, 1993).

A second reason that organizational theory has had only modest impact on organizational designs is that the large body of empirical studies on which it draws includes many studies carried out under conditions that no longer exist. For example, managers are involved in command, control, and communication—functions that have been transformed by computer-enhanced communications technology. Yet, as noted by Huber (1990), organizational theories concerning these functions have generally not accounted for the massive changes in the availability, effectiveness, and usability of technologies for command, control, and communication. Similarly, other environmental

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

forces, such as the increasing diversity of the workforce, impinge on organizations much more strongly than in previous eras.

A third reason is that some executives with broad firsthand experience, or with long histories of learning from other executives, seem to know the essence of a theory before organizational scientists articulate it. Although scientists often identify subtleties that executives may not have had the opportunity to grasp, such subtleties are often so situation-specific that they do not apply to the circumstances in which executives find themselves.

In spite of these concerns, there are important conditions under which prescriptive organizational theory can be of considerable use to organizational designers (see Donaldson, 1985, 1995). One of these is when trial-and-error learning is prohibitively expensive and applicable personal experience is unlikely to be available. For example, research shows that organizations tend to remain relatively unchanged, even as their environments shift, leading eventually to the need for radical and swift redesign (Hannan and Freeman, 1984). Unfortunately, swift redesign leaves no time for experiential learning, so redesign decisions need to be right the first time. Without the products of systematic empirical studies, many executives would have little basis for making informed choices.

The value of organizational theory as a basis for organizational design is understood best in relation to the alternatives. As we noted, in a fast-changing world, personal experience applicable to any current choice situation is unlikely to be available. Also, because the feedback from executive action is both slow and subject to cognitive and motivational biases, it is very difficult for accurate learning to occur. Thus, although the aggregate personal interpretations of experience by a team of executives are likely to be superior to any single executive's interpretation, they are unlikely to be superior to the systematically evolved theory that comes from the careful integration of the results of scores of scientific studies.

Doctrine

Doctrine consists of design principles derived from the experiences, beliefs, values, and ideologies of an organization's key leaders. Because doctrine follows from the careful review and integration, by many experts, of many experiences, idiosyncratic confounding variables and noise are reduced in their impact, and contingencies are often recognized and accounted for. Thus, with respect to experience, doctrine does not suffer from some of the problems involved in using the experience of individual managers.

It is also true that beliefs, values, and ideologies are generally extremely slow to change and often very resistant to revision in light of new data. As a consequence, the use of doctrine can lead to periods of poor organizational performance when conditions are changing rapidly.

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

Doctrine as a basis for organizational design has an advantage over the more general organizational theory, in that it is specific to a particular type of organization. It does not suffer from the low levels of accuracy that sometimes occur when highly generalized, cross-industry theories are used to predict the relationship between design and performance in specific situations. In this respect, it avoids the criticism that Starbuck (1993) would direct at prescriptive organization theory—that it does not account for the properties that make organizations distinctive.

Experience, organization theory, and doctrine each serve as a basis for the design of organizations. Because they draw on past events, they tend to perpetuate previous designs (albeit designs that led to satisfactory performance); they tend not to lead to new organizational forms. New forms or designs are appearing, however, and we turn now to a discussion of them.

New Organizational Forms

As organizational environments undergo accelerating change, it is no surprise to discover distinctively new forms of organizations emerging as managers attempt to create organizations better suited to these changes. In this section we examine several "new" organizational forms: the adhocracy or the team-based organization, the network or virtual organization, the horizontal organization, and the matrix organization (the oldest of the new forms). The first three of these new forms have so far received little empirical examination. Indeed, a reason to mention them here is to make them more conspicuous as objects and opportunities for study by organizational scientists. A second reason to note them is that, individually and collectively, they may portend the future set of organizational forms from which managers choose and which organizational scientists study for their survivability. As such, these forms can be regarded as archetypes or as new general models or templates for constructing organizations (Hinings and Greenwood, 1989).

Team-Based Organizations

In today's fast-changing organizational environments, competitive pressures and stakeholder demands have compelled many organizations to redesign large portions of their operations as team-based structures. In such structures, specialists from different domains work together to complete projects. Although sometimes a team is self-managed, generally a team leader is appointed by higher-level management. When a team's task consists of projects rather than ongoing activities, the team typically disbands after a project is completed and its members move on to other projects.

Organizations in which the temporary team structure is dominant are

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

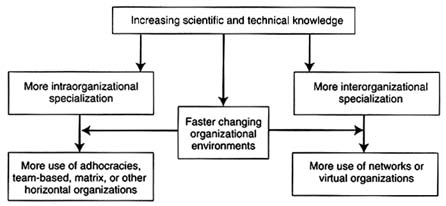

FIGURE 1-1 Drivers for new organizational forms.

called adhocracies. The adhocracy form of organization has developed in order to deal simultaneously with the coordination problems associated with intraorganizational specialization and the requirement for quick responses associated with fast-changing environments (see Figure 1-1). Not all team-based organizations are adhocracies. The term refers specifically to organizations in which the teams are temporary structures, as in the production of theatrical performances in which producers, directors, technicians, and actors come together to form a temporary company that produces a play. The teams then disband when the production has been completed and the members join other teams to produce a different play. In contrast are permanent multispecialist teams, such as professional sports teams and surgical teams in hospitals.

Adhocracies and other project-based team structures are currently in fashion and seem to be appropriate design solutions in certain situations (see Katzenbach and Smith, 1993; Mohrman et al., 1995). Widely accepted solutions have not yet been developed to the problems of team rewards, including compensation, and the maintenance of technical expertise for experts whose team assignments do not provide opportunities for technical learning.

Network or Virtual Organizations

The increases in knowledge specialization that lead to an adhocracy's intraorganizational specialization also lead to interorganizational specialization, as organizations seek to exploit niches with their own distinctive products and services. The network form has developed in order to deal simultaneously with higher levels of interorganizational specialization and the

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

greater need for fast adaptation that follows from more instability and turbulence in organizational environments (see Figure 1-1). When organizations specialize, they often are forced to limit the range of their competencies and team with other organizations with different specializations to satisfy customer needs. Such interorganizational teaming results in what is called a network organization 4 or a virtual organization (see Powell, 1990, for an overview of research on networks). Network organizations are generally formed by a "broker" who selects the member organizations and coordinates their network-related strategic activities. In some instances, only strategic planning and financial accounting are performed by the broker; all other functions, such as design, manufacturing, and advertising, are carried out by other organizations in the network.

In essence, a network organization is an integrated set of alliances. In network organizations, membership is not permanent, although if the network has a continuing market, good performance by member organizations usually leads to continuing membership. Member organizations are generally members of other network organizations. The instability of organizational environments can cause one network member to become mismatched, either as the network changes focus or as the member organization finds new opportunities outside the particular network. (For an example of creating and managing network structures, see the Eccles and Crane, 1988, study of investment bankers.)

The network organization is an extension of the concept of a vertically integrated organization that contains all necessary functional units within itself. As other organizations specialize in certain functions and become more practiced, capable, and efficient in performing them, vertically integrated organizations can eliminate their corresponding functional units and instead subcontract these functions to the external specialist organizations to form a network organization; they can then focus on their functional "core competence" (Quinn, 1992). Theories of transaction costs are a basis for prescriptions about the types of activities that organizations should conduct within their firms and those they should contract out—the "make or buy" decision (Williamson and Masters, 1995). This sequence of events can certainly occur, although a more common scenario is that of an entrepreneur or an entrepreneurial organization that sees an opportunity to engage in a large endeavor without creating a large vertically integrated or multifunctional organization, creating instead alliances with other organizations (Harrison, 1994).

Network organizations are an increasingly common supraorganizational form. As noted by Kanter (1989), they pose problems of interorganizational coordination and the development of trust; these problems and others are examined in Miles and Snow (1992) and Kanter (1994).

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

Horizontal Organizations

One of the most common and important tasks of the middle manager is coordination, yet, during the past decade or two, layers of middle management have been eliminated. One substitution for the deletion of the middle manager coordination function is to require and authorize first-line managers and operations-level personnel to coordinate work and work flow across functions. The term horizontal organization refers to the organizational form in which coordination is done by direct and prescribed interaction between persons of different units. This form of organization is employed in hospitals, when a patient is processed through a series of departments without the use of coordination by superordinate authority. The horizontal form was created in response to a demand for faster decision making and decision implementation and greater efficiencies. It goes beyond the capabilities of what has been called the "informal organization" in that it increases reliability by formalizing accountability and procedures.

Matrix Organizations

A matrix organization exists whenever there are overlapping sources of formal authority. This organizational form originated in the electronics and space industries shortly after World War II. Its adoption was fashionable for several decades, and it is still popular today.

Early in the evolution of the matrix form, problems in coordinating functional specialists caused organizations to create coordinating roles on behalf of the functional department managers. At this early stage, functional managers generally delegated no authority to the coordinator. That form has been termed a functional matrix (Larson and Gobeli, 1987). Increasing pressures for both shorter project completion times and less proprietary resource allocations from departments led to project managers acquiring more authority and attaining more influence. This organizational form is called a project matrix. The extension to a team-based organization, in which functional departments have no authority over team members during a project's life, followed.

The matrix form is a stable form in some organizations, such as the hospital industry, in which a unit manager has coordination responsibility as well as a high level of responsibility for the performance of medical wards, but functional specialists also have some level of responsibility to their function supervisor, as does a nurse to the head nurse. In other organizations, it seems to be serving as a transition form between the functional form and the team-based form. For an interesting analysis of the adoption and abandonment of matrix management in the hospital industry, see Burns and Wholey (1993).

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

Other Organizational Forms

Several additional organizational forms, not yet included in any generally accepted taxonomy and without widely accepted names, have emerged over the years in response to particular situations. Toffler (1990) describes several of them, including the following:

- Pulsating organization. This organizational form expands and contracts rhythmically. Examples are the U.S. Bureau of the Census, which expands when a census is taken; retail firms that expand and contract around holidays; and pickup crews used in film and TV production.

- Two-faced organizations. This organizational form is designed to operate in two modes, depending on circumstances. Examples include fire, rescue, ambulance, military, and antiterrorist organizations. These organizations have a shadow management for normal operations and special units or teams for crisis management. The values and cultures of the two modes differ.

- The skunkworks. This form denotes a team that is given a loosely specified problem or goal and allowed to operate outside company rules (Kidder, 1981). Official channels and rules can be ignored. This design form may be greatly creative, but success depends heavily on team member competence.

Quinn (1992) discusses decentralized organizations (as ''intimately flat" organizations), extremely dispersed organizations (as "spider's web" organizations), "inverted" organizations when all nonboundary-spanning units serve the units that interface with the customers and clients, and other new and not yet common organizational designs. As organizational environments become more differentiated, we can expect more new organizational forms, but as these environments continue to change, we can expect a sizable proportion of the new forms to pass away, as the niches for which they are well matched disappear.

Conclusions

Organizational Change

- Increases in scientific knowledge, professionalism, the performance of technologies, and demographic diversity are key features of organizational environments.

- Many major changes in organizations are prompted by changes in organizational environments, often changes that threaten organizational performance or legitimacy. Top management interprets these change, often as

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

- threats or opportunities, and determines or at least influences how the organization changes in response to these changes.

- Increases in scientific knowledge have led and continue to lead rather directly to changes in the organizational structures and processes that deal with organizational learning, decision making, and adaptation.

- Increases in scientific knowledge, professionalism, and the performance of technology are having significant impacts on organizational design and performance.

- Environmental changes that are having subtle but nevertheless significant changes in organizations are changes in the demography of society and the workplace. Increases in demographic diversity within an organization can lead to improved decision making through the introduction of a wide variety of knowledge, to a reduction in cooperation and prosocial behavior, and to improved interaction with resource controllers in the organization's environment.

Organizational Design

- The strongest driving force for organizational redesign is the necessity to adapt to a changing organizational environment.

- The most widely employed theory concerning adaptation of organizations to their environments and the internal alignment of organizational features is that of contingency or configuration theory. This perspective corrects the tendency of early organizational theorists to assume that certain universal prescriptions would be optimal for all organizations and all environments.

- The major sources of guidance for organizational redesign are research and theory, pragmatic experience and, in special cases, the existence of doctrine or overarching principles regarding "the way things are done here." Doctrine as a guide for organizational decisions has been developed most fully in the military, although doctrinal elements are apparent in many organizations. Each of these three bases for organizational redesign—theory and research, experience, and doctrine—has its own characteristic strengths and weaknesses.

- Although many organizational designs are conceivable, relatively few are encountered with any frequency. Four basic types are commonly recognized: simple hierarchies, machine bureaucracies, professional bureaucracies, and team-based adhocracies. Both hybrids, which result from a combination of two or more basic types, and supraorganizations develop as organizations attempt to address more complex tasks and environments.

- The history of individual organizations often shows a pattern of evolution and revolution. Organizations tend to alternate between relatively

Suggested Citation:"1 Organizational Change and Redesign." National Research Council. 1997. Enhancing Organizational Performance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/5128.

×

- long periods of incremental adjustment and resistance to environmental change and occasional brief periods of major redesign.

- Some organizational changes, incremental for the most part, seem to be age related. As organizations grow older, they develop greater internal specialization of roles and more coordination processes and structures.

Notes

| 1Many of the missions and roles central to the U.S. Army and other forces during the cold war are adjusting to new realities and their requirements. Although the United States will be prepared, as it was in the Persian Gulf War, to respond to conventional military threats, it is still struggling with new and unfamiliar missions such as peace-keeping and humanitarian relief. Our examination focused on the redesign of force structures and unit organizations for responding to traditional hostile threats. Although we have considered peacekeeping issues elsewhere in this report, our focus is on the process rather than the design of peacekeeping units. |

| 2The process of force development is far more complex than can or need be reported here in order to understand the basic doctrine-driven design approach used in unit design. Army force structuring and force development are accomplished in response to a National Military Strategy Document, which is updated every two years. Information on the process may be found in U.S. Army (1995). |

| 3The Army's use of mathematical modeling and computer simulation to determine the organizational design characteristics most likely to lead to high levels of performance prompts us to note that organizational and management scientists frequently use least square statistical analysis and occasionally data development analysis to determine the relationships between organizational design characteristics and organizational performance for particular groups of highly similar organizations. |

| 4Organizations and teams can be networked internally and externally with the aid of electronic networks. However, the electronic network is not a requirement for networking to occur. |

Some of the Newer Organizational Designs Might Improve the Organization

Source: https://www.nap.edu/read/5128/chapter/3

0 Response to "Some of the Newer Organizational Designs Might Improve the Organization"

Post a Comment